Study: India and Sri Lanka - A Global Sea Cucumber Crime Hotspot

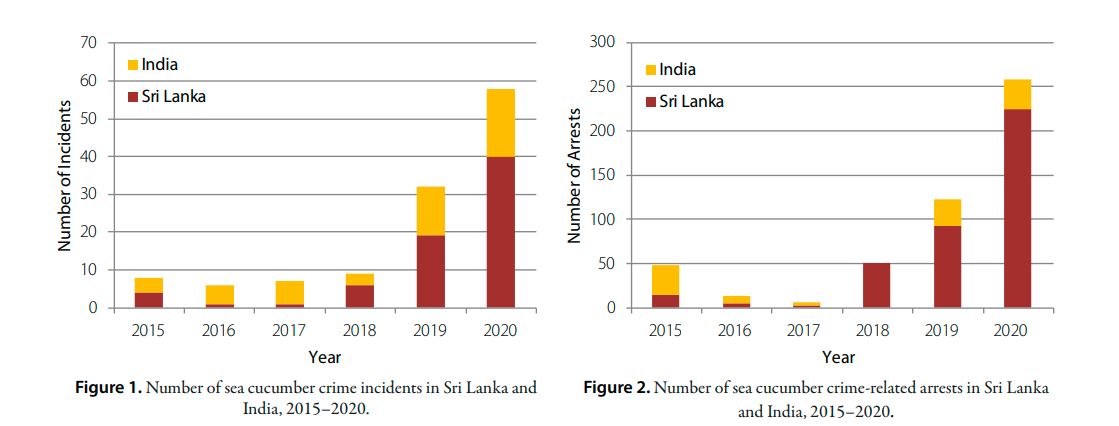

Sea cucumber poaching and smuggling have been on the rise in Sri Lanka and India, says a new article by Dr. Teale Phelps Bondaroff, director of Research for OceansAsia. The article, published in the most recent issue of the SPC Beche-de-Mer Information Bulletin, analyzes 120 incidents of sea cucumber crime in India and Sri Lanka, between 2015 and 2020.

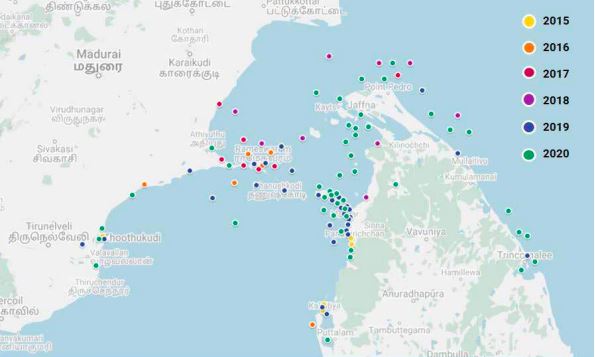

The Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay, between India and Sri Lanka, is home to a significant licit and illicit sea cucumber fishery. Smuggling and poaching are particularly widespread due to the lack of coordination between the legal jurisdictions of each country. India issued a blanket ban on all sea cucumber fishing in 2001, and sea cucumbers are protected under Schedule I of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972. By contrast, in Sri Lanka sea cucumber harvesting is permitted, but licenses are required for fishing, diving, and export. As a result, criminals frequently attempt to smuggle sea cucumbers they illegally caught in India into Sri Lanka to launder and re-export them to South East Asian markets, where they are sold for food and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

Sea cucumber is viewed as a luxury food product and is used in TCM, and the price for sea cucumber has been on the rise. Some species, like the sandfish (Holothuria scabra), can sell for as much as US$1,800/kg, and the white teatfish (H. fuscogilva) sells for US$401/kg.

Analyzing 120 identified sea cucumber poaching and smuggling incidents, Dr. Phelps Bondaroff’s study identified the following:

- There has been a marked increase in poaching and smuggling incidents in the past two years.

- Across the incidents studied, law enforcement arrested 502 people, with an average of four arrests per incident.

- Over 64.7 tons (104,531 individual animals) were seized, with an estimated value of US$2.84 million (₹20.7 crore (INR) or Rs 528.3 billion (LKR)).

- In addition to seizing live, dead, and processed sea cucumbers, Indian and Sri Lankan authorities also seized 105 vessels, seven vehicles, and considerable quantities of fishing and diving gear.

By mapping the incidents, the study identifies the Gulf of Mannar/Palk Bay region as a global hotspot for sea cucumber crime. In the past year, Lakshadweep was the location of an increased number of smuggling and poaching incidents, showing that sea cucumber crime is expanding into this remote island chain.

“When sea cucumber crimes are mapped, they clearly reveal smuggling routes connecting India to Sri Lanka. Illegally caught sea cucumbers are smuggled into Sri Lanka so they can be laundered and re-exported to South East Asian markets,” says Dr. Phelps Bondaroff.

“Sea cucumber poaching and smuggling operations are highly organized,” says Dr. Phelps Bondaroff. “Groups of fishers illegally catch hundreds of kilograms of sea cucumbers, and then smuggle them through highly coordinated networks. Smugglers and poachers often stockpile sea cucumbers in hidden sites to be retrieved later, and large consignments are then transported by sophisticated teams including lookouts and getaway drivers.”

One reason for the increased arrests and seizures in 2019 and 2020 is the increased monitoring and enforcement of sea cucumber crime by Indian and Sri Lankan authorities. India recently formed the Lakshadweep Sea Cucumber Protection Task Force and established a number of ‘anti-poaching camps’ in Lakshadweep. India also created the world’s first conservation area for sea cucumbers in February 2020 – the Dr K.K. Mohammed Koya Sea Cucumber Conservation Reserve, a 239 km2 area near Cheriyapani, Laksadweep.

“Sea cucumber crime is a form of transnational organized crime, and I am pleased to see the Indian and Sri Lankan authorities are increasingly recognizing the threat it poses,” says Dr. Phelps Bondaroff. In India, a number of cases of sea cucumber poaching and smuggling have been referred to the Central Bureau of Investigation, an agency whose jurisdiction covers law enforceable by the Indian Government, multi-state organized crime, multi-agency, and international cases.

“Cooperation is key to effectively combating transnational organized crime, and increased coordination and cooperation between Indian and Sri Lankan authorities is needed,” says Gary Stokes, Operations Director for OceansAsia. “States should ensure that penalties and sanctions serve as an effective deterrent and that they are promptly imposed. Penalties cannot simply become part of the cost of doing business, or criminal operations will continue to flourish.”

“Here in Hong Kong, we see daily shipments of sea cucumbers and other dried seafood products from around the world. The magnitude of this illegal trade is enormous,” says Stokes. “While much of the focus has been on charismatic species like sharks, sea cucumber and other less iconic species go largely unnoticed, even though they play a critical role in the survival of healthy marine ecosystems.”

About Sea Cucumbers

Sea cucumbers are echinoderms, marine animals with radial symmetry that include starfish, sea urchins, and sand dollars. Over 1,700 species of sea cucumber (Holothuroidea) have been described globally. Some 200 sea cucumber species can be found in Indian waters, and of these, about 20 are considered commercially important. Roughly 24 species of sea cucumber can be found in Sri Lankan waters, of which 20 have commercial value.

Sea cucumbers play important roles in marine ecosystems: sea cucumbers that burrow into the sea bed help rework the soil in a process known as bioturbation which helps other species flourish and is a major driver of biodiversity. As deposit feeders, sea cucumbers play an important role in nutrient cycling. Their actions reduce organic loads and redistribute surface sediment, and the inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus they excrete enhances the benthic (sea floor) habitat. As a result they are excellent bioremediators. These same actions can increase seawater alkalinity, which helps create local buffers against ocean acidification, supporting the survival of coral reefs. Sea cucumbers are also food for others species, and also have complex symbiotic relationships with others.

Removing sea cucumbers from an ecosystem in unsustainable numbers can therefore have a serious impact on that ecosystem and the species that live there. One study summarized this impact, explaining that the “overexploitation of sea cucumbers is likely to decrease sediment health, reduce nutrient recycling and potential benefits of deposit-feeding to seawater chemistry, diminish biodiversity of associated symbionts, and reduce the transfer of organic matter from detritus to higher trophic levels.”

“Sea cucumbers play a critical role in marine ecosystems, acting like earthworms of the sea by cycling material in the seabed and playing an important role in nutrient cycling. Sea cucumber crime threatens species and ecosystems, but it also undermines good governance and steals from legal fishers and governments,” says Dr. Phelps Bondaroff.